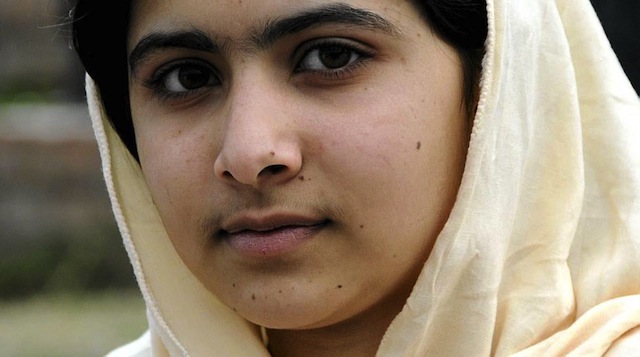

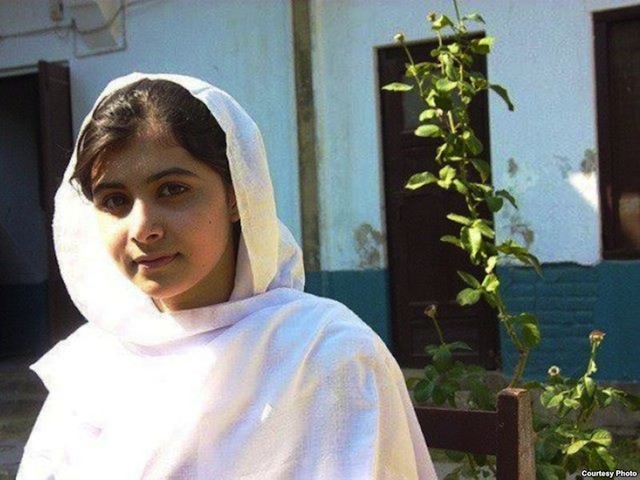

“Sometimes I imagine I’m going along and the Taliban stop me. I take my sandal and hit them on the face and say what you’re doing is wrong. Education is our right, don’t take it from us. There is this quality in me – I’m ready for all situations. So even if (God let this not happen) they kill me, I’ll first say to them, what you’re doing is wrong.” — Malala Yousafzai

This Tuesday, 14-year-old Malala Yousafzai, internationally respected Pakistani children’s rights activist and diarist for the BBC, was shot in the head and neck in an assassination attempt. Malala’s wounds, fortunately, were not fatal – she is recovering in a hospital in Peshawar after having undergone a complicated surgery to remove the bullet that was lodged close to her brain. She is still unconscious. Malala, a symbol of anti-Taliban defiance, was attacked by Taliban gunmen on her school bus, going home. Malala was targeted for “promoting secularism,” said Ensanullah Ehsan, a Taliban representative who called Malala’s work “obscenity. She has become a symbol of Western culture in the area. She was openly propagating it” and added that if she survives that they will certainly try to kill her again, “Let this be a lesson.”

Malala’s crusade for girls’ education rights began in 2009 when private schools in Pakistan’s Swat Valley were ordered to close by a Taliban edict that forbade girls from attending school. Malala, who wants to become a doctor, began keeping a diary on January 3rd of 2009, writing under the nom de guerre ‘Gul Makai’ meaning ‘face like a flower’ in Urdu. “I also like the name because my real name means ‘grief stricken,'” she wrote the night before 50,000 girls were deprived of their educations. Her diary entries chronicled three months of life under the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, a collection of Islamist extremist organizations fighting the Pakistani state. Through her writing, she exposed the trauma and anguish caused by the militants and emphasized her own attempts at continuing her education. With uncommon strength and courage, she gave a voice to all the women silenced, beaten down, brutalized and oppressed by the Taliban. In the words of Pakistani novelist Nadeem Aslam, “Pakistan produces people of extraordinary bravery. But no nation should ever require its citizens to be that brave.”

SATURDAY 3 JANUARY: I AM AFRAID

“I had a terrible dream yesterday with military helicopters and the Taleban. I have had such dreams since the launch of the military operation in Swat. My mother made me breakfast and I went off to school. I was afraid going to school because the Taleban had issued an edict banning all girls from attending schools. Only 11 students attended the class out of 27. The number decreased because of Taleban’s edict. My three friends have shifted to Peshawar, Lahore and Rawalpindi with their families after this edict. On my way from school to home I heard a man saying ‘I will kill you’. I hastened my pace and after a while I looked back if the man was still coming behind me. But to my utter relief he was talking on his mobile and must have been threatening someone else over the phone.”

Wednesday 14 January: I MAY NOT GO TO SCHOOL AGAIN

“I was in a bad mood while going to school because winter vacations are starting from tomorrow. The principal announced the vacations but did not mention the date the school was to reopen. This was the first time this has happened. In the past the reopening date was always announced clearly. The principal did not inform us about the reason behind not announcing the school reopening, but my guess was that the Taliban had announced a ban on girls’ education from 15 January. This time round, the girls were not too excited about vacations because they knew if the Taliban implemented their edict they would not be able to come to school again. Some girls were optimistic that the schools would reopen in February but others said that their parents had decided to shift from Swat and go to other cities for the sake of their education. Since today was the last day of our school, we decided to play in the playground a bit longer. I am of the view that the school will one day reopen, but while leaving I looked at the building as if I would not come here again.”

A documentary by Adam B. Ellick which follows Malala through six harrowing months during which she is forced into exile and loses her education, can be seen here.

A documentary by Adam B. Ellick which follows Malala through six harrowing months during which she is forced into exile and loses her education, can be seen here.

An interviewer asked about how she would deal with the Taliban if she were president. She answered, “First of all, I would like to talk to them. I would show them the Koran. The Koran didn’t say that girls are not allowed to go to school.” But as Pakistani journalist, Kamila Shamsie wrote, “If you view the Taliban simply through the prism of the war on terror and Pakistan and the United States, it’s possible to think the process can be reversed; policies can be changed; everyone can stop being murderous and duplicitous. For political differences, seek political solutions. But what do you do in the face of an enemy with a pathological hatred of woman? What is it that you’re saying if you say (and I do, in this case) there can be no starting point for negotiations? I believe in due process of law; I know violence begets violence. But as I keep clicking my Twitter feed for updates on Malala Yousafzai’s condition, and find instead one statement after another from the government, political parties, and the army (writing in capital letters) condemning the attack, I find myself thinking, do any of you know the way forward? Today, I’m unable to see it. But Malala, I’m sure, would tell me I’m wrong. Let her wake up, and do that.”

An interviewer asked Malala what she would say to a girl who was too afraid to stand up. She answered confidently, “so I’ll tell her don’t stay in your room, because God will ask you on the day of judgment, ‘Where were you when your people were asking [for] you?'”