Scene One: What is it, 1990? Thirteen, my sister two years younger. We’re off to Gay Pride in London (lesbian mom), and like the good sans-culottes we are, we’re making a banner out of a pillowcase we’ve stolen from the airing cupboard. We write WE’RE NOT BUT THEY ARE AND WE THINK IT’S JUST COOL in sprawling felt-tipped pen and decorate the border with clumsy whales (whales are also an issue dear to our hearts). The effect of charming juvenile solidarity is spoiled when we begin to squabble while watching a drag queen dressed as Thatcher climb a lamppost. We’re both very keen on gay (male) aesthetics; most likely the only kids in our neighborhood who read Derek Jarman, Dale Peck, Gary Indiana, Dennis Cooper (where the hell do we get these things? Well, I get them via Kitty, but she’s eleven).

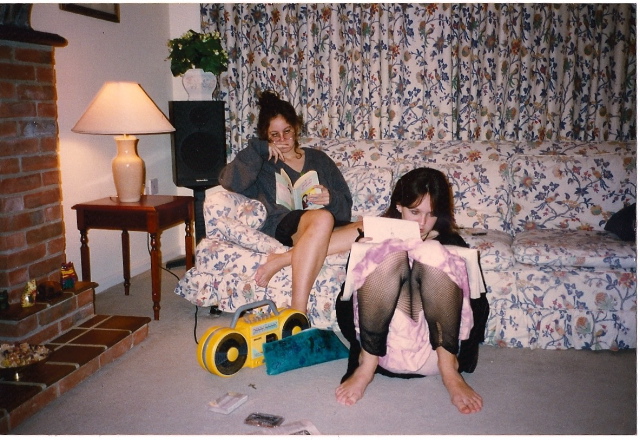

Scene Two: 1993. Let’s say I’m fifteen, spotty, irritable. Kitty and I see Huggy Bear playing ‘Her Jazz’ on The Word, a late night pop culture show we’re probably banned from watching. The singer has a bright red bob, the bass player a 60s shift and massive shades. Riot grrrl is like a fistful of firecrackers going off in my face, which is to say I’m in. Fast process from spectator to participant. I find out (how? No internet. Music mags, I guess; Melody Maker, Select, sometimes, grudgingly – too macho, too dull – NME) the names of some zines, write off for them, quickly make my own. It’s a revolution by way of the postal service. I still remember the bliss of those parcels, packed with presents: sweets and water pistols, mix-tapes with collaged covers (CWA’s magnificent ‘Only Straight Girls Wear Dresses’, God is My Co-Pilot’s ‘Down Down Baby’) and page after page of scribbled letters.

What were they called? Drop Babies. Asking For It. Stinkbomb. Honeykids. Sweet Sixteen. Dipper. Violet. When I Grow Up I Want to be Bobby Gillespie. Paradiso (these last two queercore, and beautifully produced). Mine was Blah Blah Blah: drawings of boys that had annoyed me or cartoon girls with guns, gig reviews, haphazard rants against the patriarchy or the woes of living in the suburbs. I made my dad photocopy it in his office (one Christmas, a good decade later, he brought out the copies he’d squirreled away). Later, I graduated to A Dead Girl’s Blues, which was in colour and fancier, with stream-of-consciousness riffs about stealing flowers and driving cars at night.

The bands sprang up just as effortlessly, unpractised, cobbled together, an aesthetic of paper and glue and bashed out bass chords. We used to race up to London on the train to see them – Pussycat Trash, Bikini Kill (‘Rebel Girl’, what an immaculate song), Skinned Teen, Babes in Toyland, Blood Sausage, God is My Co-Pilot, Linus, Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy, the Headcoatees. Where? Rough Trade, Conway Hall in Red Lion Square. There was a song about Keanu Reeves that everyone liked. Lots of screaming. Lots of girls with bare legs and short skirts, playing drums, drawing pictures, being buddies with each other. Paper and glue and bashed out bass chords. Homemade bedroom revolutionaries, Tank Girled up on attitude, in skinny rib sweaters and army boots. It taught me how writing should be: fast, intimate, urgent; a firecracker in your heart, an explosion of glitter that stops you dead.

—Olivia Laing is a writer and critic. She’s the former deputy literary editor of the Observer and her first book, To the River, is published by Canongate.