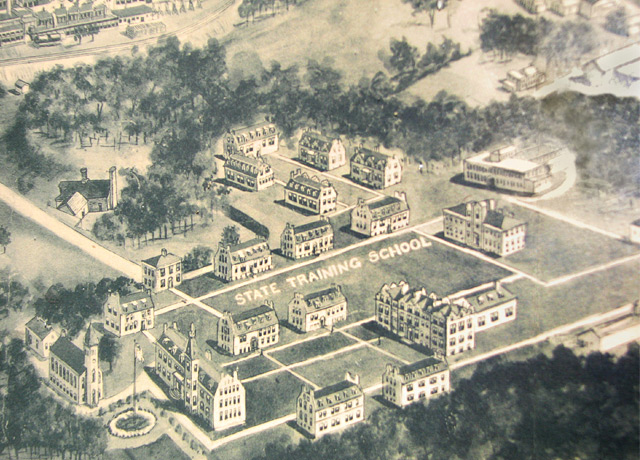

The New York State Training School for Girls was established in Hudson, New York in 1904 as a new establishment for the internment of “incorrigible” girls between the ages of 12 and 15. Many of the girls were not criminals, but rather orphaned, abandoned, abused or otherwise misunderstood young women sent to the school by the court or by their families. At its height, the Training School was home to more than 400 girls. In 1915, John H. Delaney, Commissioner of the New York Department of Efficiency and Economy, described the mission of the school: “To accomplish the reformation of wayward girls, to give destitute girls or girls having had improper guardianship right ideas concerning life and its duties…by persuasion and not by punishment.” The school closed its doors in 1975.

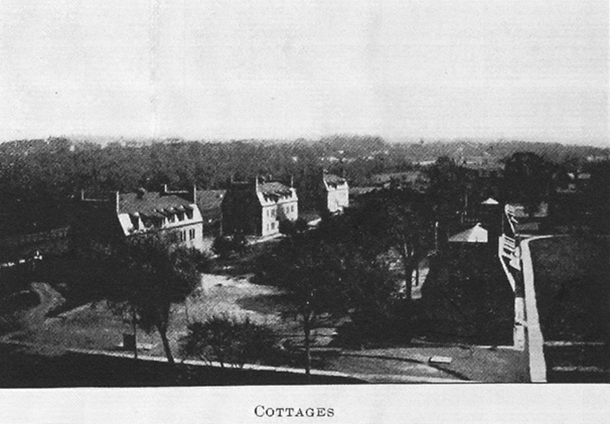

The girls were housed in 17 “cottages,” meant to emulate home life as closely as was possible in a juvenile correctional facility. In 1906, the first superintendent of the school, Hortense V. Bruce, voiced her rationale for the cottage system: “It gives something approaching a home life and this the congregate system cannot do. The smaller the group, the more individual attention the child may have, the less will there be a danger of its becoming only a cog in a wheel of routine, the more freedom will there be for the natural way of gaining knowledge by experience and finally the more it will receive and give love, sympathy, and understanding.”

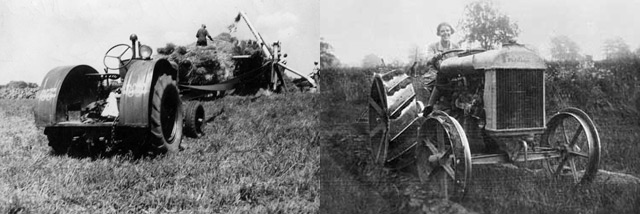

In 1923, Superintendent Fannie French Morse rented a farm nearby the school, believing that manual labor would assist in the girls’ rehabilitation.

In 1923, Superintendent Fannie French Morse rented a farm nearby the school, believing that manual labor would assist in the girls’ rehabilitation.

“The incorrigible, the emotional, the neurotic, the girl confused with the very tangle of circumstance – in the stabilizing and restoring influences of the farm life many a one can find balance and relief. To the restless girl, calling for another interest, another experience, another adventure before the last is scarce complete, the numberless and shifting interests and movements of the farm life furnish an almost exhaustless source.” — Fannie French Morse

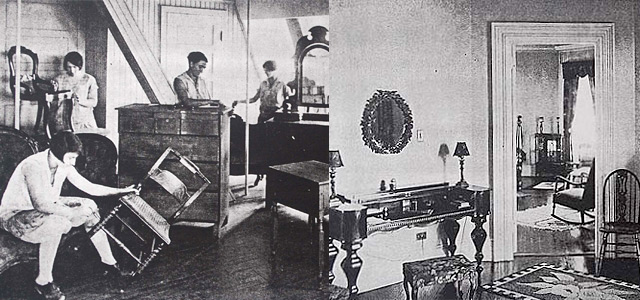

Prisoner labor was not confined to farms — some of the girls were trained to remodel the Superintendent’s home in the 1920s. According to one of the Training School’s Annual Reports, the renovation was “largely the work of specially trained girls who find through this medium of meeting the need of the Institution an applied training in their course in Interior Decoration.”

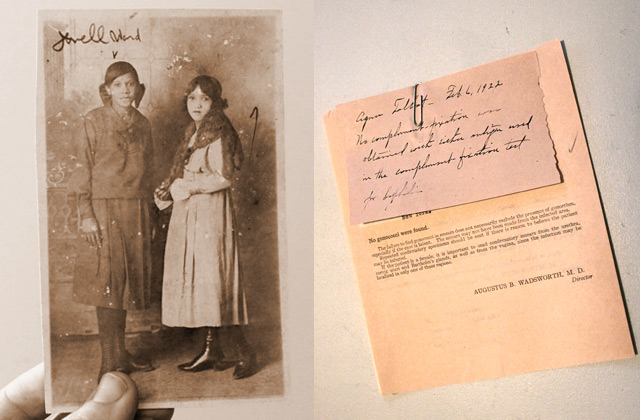

The girls were carefully monitored by doctors, who documented their personal history, work history, family, reasons for commitment to the Training School, and physicality. Over the years, the school became an important site for new research in sociology and psychology, though there were accusations that the penal practices — which included solitary confinement — were too harsh.

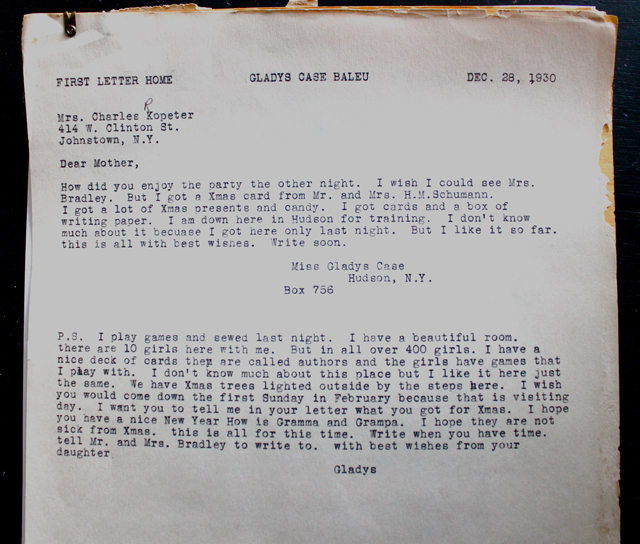

The “First Letter Home” from one of the girls to her mother, just after Christmas in 1930.

Social research photographer Marion Palfi visited the school in 1946. Her images of the girls were published in a nation-wide photographic survey of children and poverty called Suffer Little Children.

On her time at the Training School in 1946, she wrote: “At the time, 15 girls were in ‘solitary’ in the ‘discipline’ cottage. The first 10 days the girls received bread and milk for two of their three meals. One girl spent 81 days in solitary confinement, aside from periods when she was let out to scrub the floors in the corridor. One of the girls was talking to herself. The matron was very annoyed and said to her through the door: ‘You know you may not talk now – it is rest period.’ Girls were sent to the discipline cottage for running away, breaking other rules or for being too emotionally disturbed.”

One of the most famous inmates of the Training School was none other than Ella Fitzgerald. A cast-aside orphan with no where to go, 16-year-old Ella was sent to the school by a court order in 1934 and stayed for nearly a year. She was guilty of nothing more than being homeless and alone. Of the 460 residents at the time, 88 were young black women. They were segregated from the rest of the girls and regularly beaten. Thomas Tunney, the last superintendent of the school, wrote that Ella “had been held in the basement of one of the cottages once and all but tortured.” Another teacher, E. M. O’Rourke, remembered her as a model student — “I can even visualize her handwriting — she was a perfectionist.” Less than a year after she left the school, Ella would go on to win a talent contest at the legendary Apollo Theater in Harlem. She refused to speak of her experiences at the school for the rest of her life.

The Prison Public Memory Project, a Hudson based organization that aims to “build public memory and safe spaces” so that people can talk and learn about “the complex and contested role of prisons in communities and society,” is spearheading an effort to uncover the history of the New York State Training School for Girls. There is much more information about the school, including photographs and interviews, available on their website.

Teenage is screening tonight in Hudson, New York as part of the Basilica Hudson film screening series.

Special thanks to Aily Nash, Melinda Braathen and Tracy Huling for all of their assistance and guidance with this post!

All images and quotes via Prison Public Memory Project.