Barbara Newhall Follett published her first novel The House Without Windows, at the age of 12. Her second novel, The Voyage of the Norman D., was published and critically acclaimed when she was 14. At the age of 25, Barbara left her apartment with $30 (after fighting with her husband) and was never seen again.

Follett was born in New Hampshire, the only child of two literary critics and essayists, in 1914. Her parents home schooled her so that she could develop her passions, which were mainly nature and writing. At the age of four she became fascinated by the clicking of her father’s typewriter and soon began writing poetry. At five she wrote to a friend, Mr. Oberg:

The goldfinches come every afternoon and eat their supper on the clump of bachelor’s-buttons right on the left-hand side of the path that leads from the back door to our road. There are ten goldfinches, five males and five females. Before they eat their suppers, they sit on the clothesline and swing in the breeze. I wish you could be here to see them. Day before yesterday Daddy killed a snake in the potato-patch; then he threw the snake away with a stick, and then he threw away the stick. The next day Ding [Barbara’s grandmother on her mother’s side, who lived with the family] and I went down Ridgeview Place, and there were the snake and the stick. The snake was about three feet long.

A poem written by Barbara at age 7:

When I go to orchestra rehearsals,

there are often several passages for the

Triangle and Tambourine

together.

When they are together,

they sound like a big piece of metal

that has broken in thousandths

and is falling to the ground.

She didn’t have many playmates – her best friends were animals. In 1922, at the age of 8, she wrote again to Mr. Ogberg:

I pretend that Beethoven, the Two Strausses, Wagner, and the rest of the composers are still living, and they go skating with me, and when I invite them to dinner, a place has to be set for them; and when I have so many that the table won’t hold them all, I make my family sit on one side of their chair to make room for them. My abbreviation for the Two Strausses is the Two S’s. Beethoven, Wagner, and the Two S’s have maids; Beethoven’s maid’s name is Katherine Velvet, Wagner’s maid’s name is Katherine Loureena (she got the name Loureena when she was a little bit of a girl because she loved to skate in the Arena), and Strauss’s maid’s name is Sexo Crimanz… Now I am going to tell you about a funny accident that Wagner had. One morning when I had two chairs set out, one for Beethoven and the other for Wagner, I hadn’t pretended long enough to get my family used to them, and Daddy suddenly grabbed the chair that Wagner was sitting in, but I held on to it squealing: “Hey, that’s Wagner’s chair!” Then he went around to Beethoven, and I was looking suspiciously at him all the time. But he turned around again and didn’t bother Beethoven. I suppose that when he got around there, he thought that Beethoven was there.

The same year she wrote a poem told from the point of view of a little kitten named Verbiny, in Verbiny’s own language, Farksoo.

Ar peen maiburs barge craik coo

Peen yars fis farled cray pern.

Peen darndeon flar fooloos lart ain birdream.

Afee lart ain caireen ien tu cresteen der tuee,

Darnceen craik peen bune.

I will now translate it as best I can.

As the (and maiburs means a flower that comes in May) begin to come,

The air is filled with perfume.

The dandelion fluff floats like a (and birdream means something very beautiful).

Also like a fairy in her dress of gold,

Dancing to the wind.

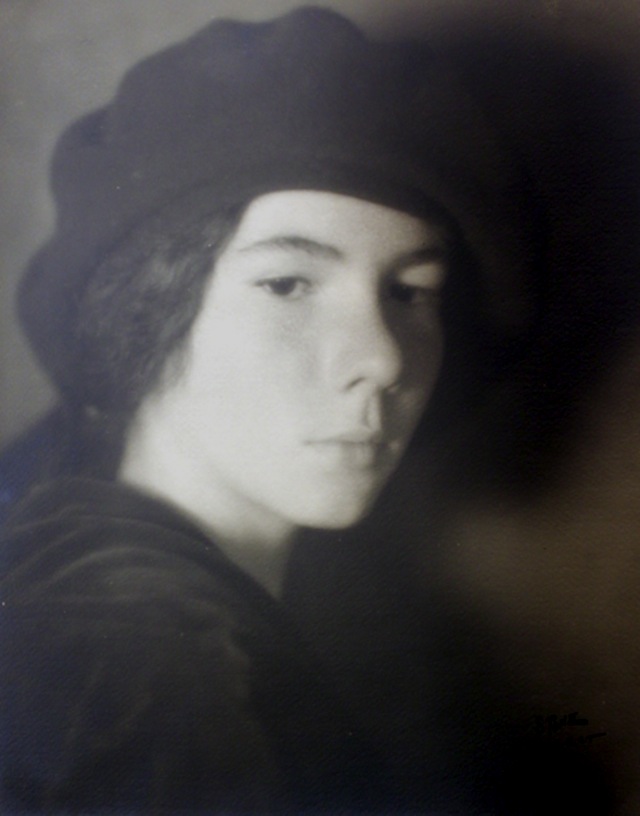

Sil – what a beautiful suffix. Below, Barbara, a fairy in the ferns.

Barbara created the kingdom of Farksolia, a kingdom with a past ruined by war. Farksolia narrowly escapes total depopulation and it’s future is to be determined by a six year old Eepersip, and a baby. She wrote this story as a present for her mother on Barbara’s 9th birthday (it was her customs to give other gifts on her day). Sadly, their house burned down and all copies were destroyed. But Barbara rewrote it a few years later and it was published by Knopf in 1927.

This is the notice that Barbara had pinned on the door of her office while she was writing (the first version that was burned):

NOBODY MAY COME INTO THIS ROOM IF THE DOOR IS SHUT TIGHT (IF IT IS SHUT NOT QUITE LATCHED IT IS ALL RIGHT) WITHOUT KNOCKING. THE PERSON IN THIS ROOM IF HE AGREES THAT ONE SHALL COME IN WILL SAY “COME IN,” OR SOMETHING LIKE THAT AND IF HE DOES NOT AGREE TO IT HE WILL SAY “NOT YET, PLEASE,” OR SOMETHING LIKE THAT. THE DOOR MAY BE SHUT IF NOBODY IS IN THE ROOM BUT IF A PERSON WANTS TO COME IN, KNOCKS AND HEARS NO ANSWER THAT MEANS THERE IS NO ONE IN THE ROOM AND HE MUST NOT GO IN.

REASON. IF THE DOOR IS SHUT TIGHT AND A PERSON IS IN THE ROOM THE SHUT DOOR MEANS THAT THE PERSON IN THE ROOM WISHES TO BE LEFT ALONE.

Barbara writes to a friend about when she received the letter of acceptance from Knopf:

I simply threw myself on the floor and screamed, either with fear for what it might contain, with joy for getting it at last, or with terrific excitement of the whole thing. There is a feeling, after you have been waiting a long time for anything, there is a feeling that, when it really comes, it must be impossible— a dream—an optical illusion—a cross between those three things…

Now: “What doo zhoo fink???” It is Eepersip, The House Without Windows, my story, my story in New York, with the Knopfs, to be published!!… published!!!!!!!!

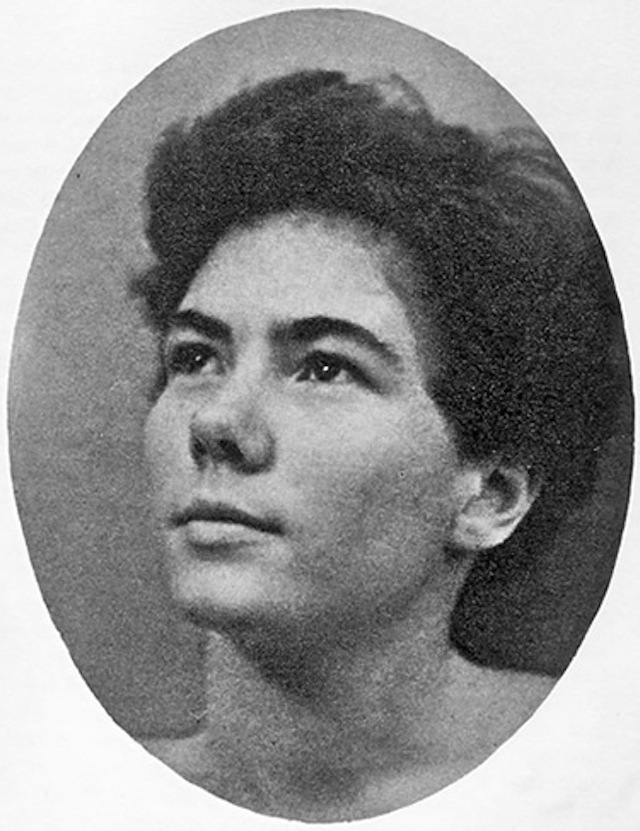

In 1927 she convinced her parents to let her board a schooner sailing from NY to Nova Scotia and work as a hand deck. Her letters and reflections on the voyage became The Voyage of the Norman D. Within days of its publication, her father (who she was devoted to and depended on for creative support), divorced her mother. It was a major blow to Barbara. She pleaded with her father to come home, but to no avail. You can read a letter she wrote to him here. After her father’s departure, she and her mother went sailing all over the world – Fiji, Barbados, Hawaii, all over. She fell in love with a crew member named Anderson who no one in her family approved of and chopped off all her hair on her 16th birthday. …One of the best afternoon’s works I ever accomplished—or perhaps ever shall, she wrote.

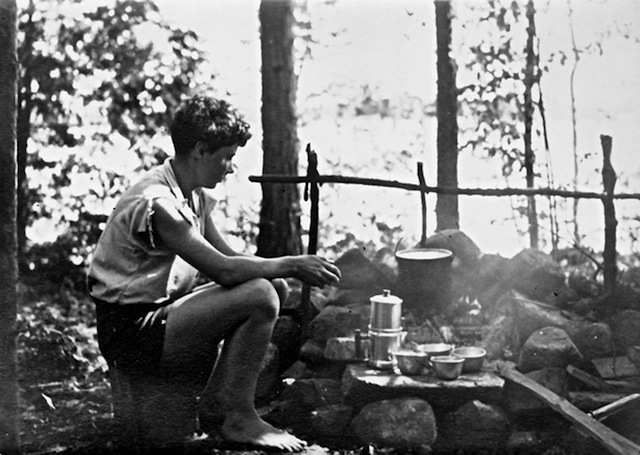

Above, camping in Maine. Below, an except from The Voyage:

Above, camping in Maine. Below, an except from The Voyage:

I spoke to the captain first of all, but very vaguely and dreamily, gazing about me—fascinated, enraptured, all the time. I looked at the long, huge booms, with the sails frapped closely round them; at the great, splendid masts; at the many ropes descending over blocks and made fast on belaying pins along the side of the boat; at the double and triple sheet blocks; and, above all, at the ratlines and shrouds, into which I longed to go up. The next minute I had jumped upon the spanker boom and crawled along to the very end, hanging slightly over the water, where I supported myself by one of the wire lifts.

“Oh,” said the captain, “I see you’re a girl as likes to climb around.”

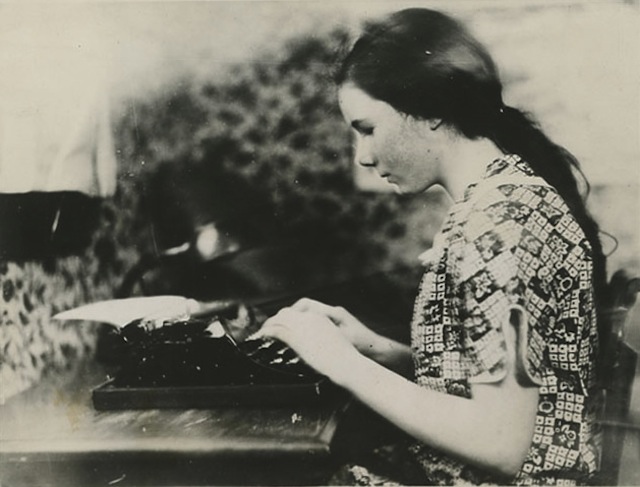

Her father left his family with very little. After Barbara and Helen’s adventures sailing the seven seas, they were broke. Barbara ran away from where they were staying in Pasadena and hid in a hotel in San Francisco to write poetry. A missing persons report was filed. The twice published novelist was working as a typist to get by.

My dreams are going through their death flurries. I thought they were all safely buried, but sometimes they stir in their grave, making my heartstrings twinge. I mean no particular dream, you understand, but the whole radiant flock of them together—with their rainbow wings, iridescent, bright, soaring, glorious, sublime. They are dying before the steel javelins and arrows of a world of Time and Money.

While working as a typist, she would wake up early to work on her next book Lost Island, about a NY couple that gets shipwrecked on a desert island. It begins:

Not even a cat was out. The rain surged down with a steady drone. It meant to harm New York and everyone there. The gutters could not contain it. Long ago they had despaired of the job and surrendered. But the rain paid no attention to them…New York people never lived in houses or even in burrows. They inhabited cells in stone cliffs. They timed the cooking of their eggs by the nearest traffic light. If the light went wrong, so did the eggs…

“I don’t like civilization,” she said, to the rain.

Through a span of six years, Barbara eventually stopped writing. She had no support from her family or the publishing industry. She eloped with an outdoorsman named Nickerson Rogers and they went backpacking around Europe together. She was happy for awhile, but became utterly tormented in their relationship.

There is somebody else…I had it coming to me, I know. On the surface things are terribly, terribly calm, and wrong…I still think there is a chance that the outcome will be a happy one, but I would have to think that anyway, in order to live; so you can draw any conclusions you like from that!

On the evening of December 7, 1939, Barbara left their apartment after fighting. She was never seen again.

You can listen to an episode on NPR about her here.

You can get all sorts of interesting information about Barbara and read a lot of her work and see more photographs at Farksolia.org

You can buy a copy of Lost Island here.