Right now Jamie and I are trying to finish the illustrations for our 2012 wall calendar, which is all about walking. I’ve been working on the cover and wanting it to be a bit pop, vintage looking, and to reflect walking as a contemplative act, not just exercise.

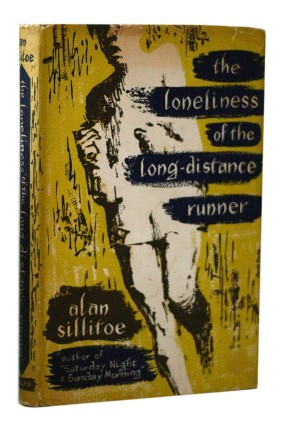

In trying to find the right tone, I started thinking back on the book covers and film design for The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. It is a story that is generally packaged with sparse graphics, masculinity, Britishness and the look of school years. My flimsy paperback version has got a pair of muddy plimsolls on the cover. The opening sequence in Tony Richardson’s film is so lonely feeling I can feel it in my teeth.

So I have been thinking about walking for months, and now I am thinking about running. The way that Tom Courtenay runs in the movie somehow gives a physical life to the feelings of confusion and resentment that one experiences as a teenager. He’s a very physical actor, as you might also know from the wonderful Billy Liar. In Loneliness, the way he moves, and the way he is filmed, evokes the space of running, the mental trajectory, the notion best described by the story’s perfectly poetic title.

In Alan Sillitoe’s original short story, the main character, called Smith, is a young thief who knows how to run, because he knows how to run away. “Running has always been made much of in our family, especially running away from the police.” Still, he is caught, and sentenced to a borstal in Essex, where his talent for running is quickly owned by the governor, who sees in Smith his one hope to win a blue ribbon. Smith becomes the governor’s prize racehorse. He gets up at five o’clock and is let out of the gates to practice, and within this routine is laid out one of the central metaphors of the book:

You might think it a bit rare, having long-distance cross-country runners in Borstal, thinking the first thing a long-distance cross-country runner would do when they set him loose at the fields and woods would be to run as far away from the place as he could and get on a bellyful of Borstal slum-gullion — but you’re wrong, and I’ll tell you why. The first thing is that them bastards over us aren’t as daft as they most of the time look, and for another thing I’m not so daft as I would look if I tried to make a break for it on my long-distance running, because to abscond and then get caught is nothing but a mug’s game, and I’m not falling for it. Cunning is what counts in this life, and even that you’ve got to use in the slyest way you can; I’m telling you straight: they’re cunning, and I’m cunning. If only ‘them’ and ‘us’ had the same ideas we’d get on like a house on fire, but they don’t see eye to eye with us and we don’t see eye to eye with them, so that’s how it stands and how it will always stand.

The end of the story I’ll leave for you to discover. In the meantime, I’m thinking about running and its relevance to the youth sensibility and youth culture. I’m thinking about Running Away and Born to Run and the metaphor of freedom and escape that the action imparts in song. And particularly in the case of moving through the bleak British landscape, as a poetic device, and what that brings to mind immediately is Stuart Murdoch, the lead singer of Belle and Sebastian, who is a runner himself. His band may have the image of a bookworm who never leaves the bedroom, but running is actually consistent with the lyrics’ introspective nature. It’s an individualistic and even intellectual pursuit. And “the stars of track and field,” as he sings, “you are beautiful people.”

That said, I am not a runner myself. When I was very young, I was rather fast. This is back when I was growing up in America. I remember how proud I felt when I was moving up the soccer field with the ball at my feet, and a boy named Mike was trying to keep up with me, and he panted, “you’re such a fast runner.” Mike was one of the first to get his pubic hair, and he paraded around the showers showing off his wiry forest, under the hawk eyes of our coach, who was possibly lecherous (considering how insistent he was on “making sure” we all took showers by watching us vigilantly). On the occasions when the coach wasn’t looking, Mike would do something crazy, which was to slide around on the wet floors, underneath the maze of partitions that made up our individual showers. It made me feel claustrophobic just to see him do it. And then all of a sudden you’d have to jump aside because he’d be sliding at your feet, the bush of his armpits and crotch triumphant.

And here he was, calling to me on the field, “I can’t keep up with you!” And that was maybe the closest I got to feeling the elation of running (for as the years passed and we ran the track, I inevitably joined the kids who just walked at the rear of the group, talking about the mystical singer from The Sugarcubes and smoking cigarettes).

But for now, here I was, the fastest runner on the field. The thing is, I was clumsy at sport. So when I did get to the goalpost, with no one to bother me and with time to spare, I fumbled. I simply couldn’t muster the right angle to properly send the ball in. And soon enough, the hordes of boys were upon me, my own teammates lambasting me for missing the perfect opportunity to score. We all knew it would happen.

Maybe I should have been a long-distance runner. If it was just that, no teammates, no ball, I would have won. But my high school story isn’t about winning. They say team sports are good for youth, but does that apply to those who are picked last?

I’ll leave you with a final image, which has stayed with me for years. I wasn’t a teenager myself anymore. We were on a trip up the West Coast and we were in a quiet little town in Oregon, clean as only Oregon can be, with a coast of soft, white sand, and out on the water, the rock that featured in The Goonies. And we sat on the beach and looked at that rock and played with the sand through our fingers and talked. And walking back to the campsite through the empty streets, we saw the teenage boy, shirtless and perfect looking, running in the the road. We had seen him earlier in the evening going one direction and here he was again, looping the town, still in the very middle of the road after darkness had fallen. It was so silent you would hear a car from a mile off, so no danger there. And in the stillness, you could feel that he owned this town. And I thought of the play Our Town and of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. I thought of the great American trope of the town’s ablest young man, whose next and necessary step would be to leave: To go to university, maybe to a big city, to become a part of things. In that moment, shirtless in the night in the middle of the road, he still belonged to the town he grew up in, or it belonged to him. But not for long. You could just feel that it was his last summer there, and that he would very soon be running away.

—Jeremy Lin is one-half of the art partnership Atherton Lin. The current task at hand is to finish the 2012 wall calendar, entitled BOOTS ON & READY. He lives in East London, where he walks, not runs.